By Erik Kwakkel (@erik_kwakkel) from medievalfragments:

This blog entry focuses on a book fragment I encountered in Leiden University Library earlier this week while studying twelfth-century material with my research team.

As discussed in an earlier blog, after the invention of printing many handwritten books from the medieval period were cut up to be recycled for use in bookbindings, for example to support the bookblock as seen here. Cutting up printed books was a far more infrequent practice, it seems; rare even. This is in part, of course, because such books were made of paper, a much more fragile material than the parchment sheets from medieval books, and therefore less suitable for holding together a bookbinding. This is the story of such a rare printed fragment. And what a story it is!

According to an accompanying library note, the fragment in question (as well as two other cuttings from the same book) were used to support the binding of a bible printed in Antwerp in 1614. All three of them contain traces of binder’s glue. They are the remains of a Dutch book that clarified the Latin Mass, given such phrases as “When the priest receives the Holy Sacrament, and what it means.”

Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, BPL 3254, unnumbered fragments (Photo: Erik Kwakkel)

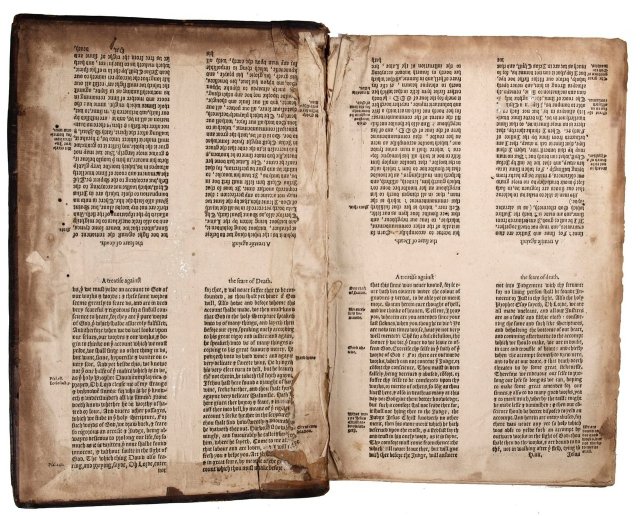

A mere glance at the fragments reveals a most remarkable feature: they were never part of an actual book. If you look carefully, you notice how part of the text can be read as it is shown in the image, while another part can only be read if you turn the page 180 degrees. In other words, the fragments are parts of sheets that were uncut and unfolded. Come again? A printed sheet of paper coming off the press usually consisted of two, four or even eight pages on the one side, and as many on the other. When both sides were printed the sheet was folded into a quire, the building block of the book. That never happened in this case, likely because the sheet was rejected by the printer and thrown in the proverbial bin – after which it was likely sold to a bookbinder and recycled as waste paper. Uncut printed sheets were rare at the time, but even rarer today. Fortune has it that I recently encountered another specimen, kept in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington (check out this blog I wrote about it).

Washington, Folger Library, STC 25004 c. 2 (binding waste): uncut sheet from a 16th-century print shop (Photo: Folger)

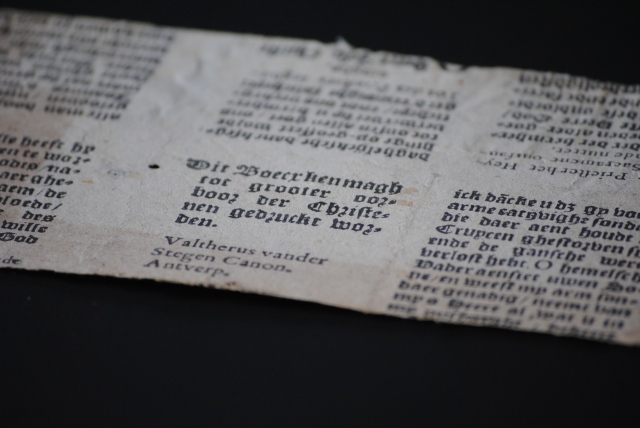

The Leiden fragments are also special for another reason – one that sheds light on early-modern book culture in a different way. Note how the smallest snippet contains a brief section printed in a slightly larger typeface (see image below). It reads: “This book may be printed for the greater good of Christians” (“Dit Boecxken magh tot grooter oorboor der Christenen gedruckt worden.”) This intriguing colophon-like message has nothing to do with the contents as such, but reflects the book as an object. In what was likely the last page of the book, it tells the potential buyer that it was safe to purchase this book. Underneath it we read, in a different typeface: “Valtherus vander Stegen Canon. Antverp.” [Walterus vander Stegen, Canon in Antwerp]. What gives?

Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, BPL 3254, fragment 1 of 3, detail (Photo: Erik Kwakkel).

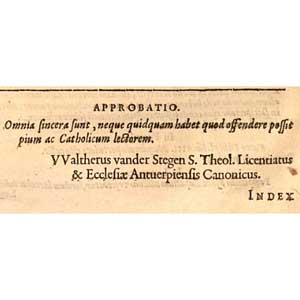

The name at the bottom forms the key to unlocking the mystery of this message. Walter van der Stegen (d. 1588) was canon at Antwerp cathedral and a member of the Inquisition. In that capacity he checked what printers were printing. He is known, for example, from the correspondence of the Antwerp printing house Plantin Moretus, with whom Van der Stegen was befriended (more about this here, at page 114; and here). As representative of the Inquisitor, Van der Stegen would give his blessing to certain editions, while making sure others did not see the light of day. The words in the Leiden fragment is his stamp of approval, almost literally: it indicates that the production of this particular book was granted by the Inquisition. Such approbations needed to be included in printed books after the Spanish authorities had regained control in the Low Countries. Latin books approved by Van der Stegen carried a Latin variant of the “stamp”. Here is one found in Justus Lipsius’ Collected Works, which bears the heading approbatio (giving approval):

Colophon with Vander Stegen’s approval in Justus Lipsius, Opera omnia (Antwerp: Johannes Moretus, 1600)

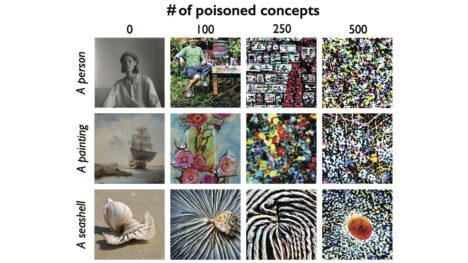

Thus the tiny fragment and its two siblings bear unexpected evidence of some of the problems encountered by early printers: censorship and the affiliated fuss of seeking and printing Church approval; as well as the complexities of a new medium that involved printing several pages at the same time and on different sides of the paper – producing rejects, from time to time. What I find most astonishing, however, is that one of the three surviving snippets of the lost book should contain the approbation that gave life to the object it was once part of. The Inquisitor would have approved.

Post scriptum: I wish to thank Paul Hoftijzer (Leiden) for his input regarding printed approbations.